The legal implications of sham transactions

A sham transaction is a business deal entered into parties for the purpose of deception, like to escape a tax liability or in other words simply to avoid paying tax. Since long the courts in the country have been using “the sham transaction principle” to reject deals done to escape income taxes.

A sham transaction is a business deal entered into parties for the purpose of deception, like to escape a tax liability or in other words simply to avoid paying tax. Since long the courts in the country have been using “the sham transaction principle” to reject deals done to escape income taxes.

The question whether a deal is a sham transaction or not is a factual one and the burden of proof is upon the taxpayer in the process of abatement.

Tests to determine whether a transaction is sham or not:

Assessees enter into sham transaction primarily for avoiding tax. For detecting whether a deal is sham transaction or not courts often apply a two-fold test of which the first one checks whether the transaction has any economic interest other than availing a tax benefit, which is actually the “objective” test. The second one checks whether the transaction has any business purpose other than availing a tax benefit, which is the “subjective” test.

Many courts in India have rejected the rigid two-step tests. Practically courts consider the aspect whether the transaction has any practical economic effect other than projecting income tax loss.

Purpose of rejecting sham transactions:

If an assessee uses a “colourable device” such as sham transaction to avoid taxes, it is often treated as tax evasion rather than tax planning.

View of the Apex Court:

The Apex Court of India, in the case of Union of India v. Azadi Bachao Andolan, held that while a colourable means have resulted in a sham transaction, that does not mean that tax planning would not be allowed as per law.

It observed in the Vodafone case by the Hon’ble Supreme Court that tax planning within the limits of law could be allowed as long as it does not amount to a colourable means.

It was further observed that with the recent legislative amendments and the introduction of indirect transfer tax provisions along with the general anti-avoidance rules, there has been a shift towards a substance based system. The new rules empower the income tax authorities a full discretion in taxing “sham transactions” and even denying tax benefits.

Now courts can rightly deny tax benefits in issues relating to tax avoidance in cases where the majority of the business deal does not actually take place.

Decisions on sham transactions:

In Consolidated Finvest & Holdings Limited v. ACIT, the Income Tax Appellate Tribunal, Delhi examined many transactions between two sister concerns which resulted in capital loss in the hands of one and found that there was no avoidance of income tax.

The assessee gave many advances to a sister concern, Jindal Polyfilms Limited which was a public company promoted by the assessee. When the assessee was unable to repay such loans, it restructured the transaction by issuing securities. After the sale of such securities the assessee claimed long term capital loss on the transactions. The assessee also claimed carry-forward of the loss in its income tax returns.

The assessing officer disallowed the loss on the ground that the transactions were “sham” and purported to transfer funds from a sister concern to another merely by showing a loss.

The assessee contended that at the earlier stages of the transaction, the tax authorities did not consider them as sham. Moreover, the facts of the case were different from the facts of the case relied upon by the income tax authorities.

The Tribunal held that the mere fact that one of the transaction has resulted in capital loss for the assessee would not make the chain of transactions a sham.

Differences between “benami” and “sham transactions”:

Recently, the Orissa High Court in the case of Keshab Chandra Nayak v. Laxmidhar Nayak, summarized the differences between “benami” and “sham transactions”.

The “benami” transaction is one in which there is a valid transfer involving the passing of title in the transferee, but in the sham transaction, there is no valid transfer though the deed involved in the transaction gives the transferee a title in the property.

Sham transaction takes place when there is no consideration involved in the transfer. If the transferor wants to challenge the validity of the transaction, he needs to seek cancellation of the document as so long as the document stands, the transferee would hold the title to the property.

In case of benami transaction, the document is a perfectly valid document, but the main issue involved is who the real owner of the property. The doubt remains is whether it is the transferee as has been stated in the deed as the transferee seems to be a benami. In such a case, the aggrieved person does not demand cancellation of the sale deed as if it is cancelled; he would not acquire any right, title or interest over the property in question.

On the other hand, in the case of a sham transaction, the aggrieved person may ask for cancellation of the deed where the transaction is void.

Can an assessee pay House Rent to his parents and claim relief? Would there be any legal complications?

Can an assessee pay House Rent to his parents and claim relief? Would there be any legal complications?  Boost Your Business & Reduce Taxes: A Guide to Maximizing Benefits Under Section 80JJAA

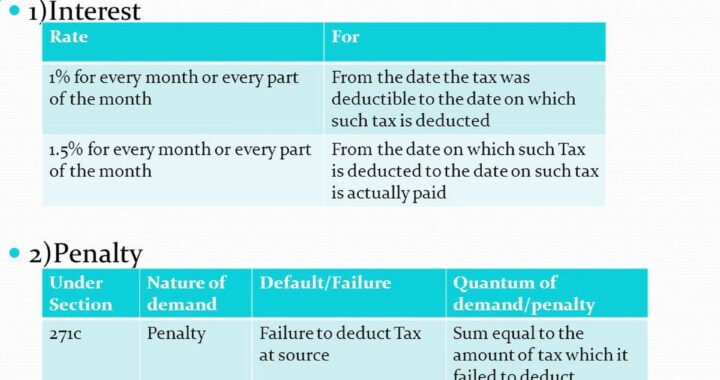

Boost Your Business & Reduce Taxes: A Guide to Maximizing Benefits Under Section 80JJAA  What is remedy to taxpayer if the Tax deductor fails to deposit the TDS or fails to file TDS Return

What is remedy to taxpayer if the Tax deductor fails to deposit the TDS or fails to file TDS Return  What is Income Tax Liability on Income from trading in Future and Options

What is Income Tax Liability on Income from trading in Future and Options  The Importance of Filing Your Income Tax Return on Time: A Financial Must-Do

The Importance of Filing Your Income Tax Return on Time: A Financial Must-Do  Is Addition made by Assessing officer on basis of mismatch between AIR and F26AS Justified

Is Addition made by Assessing officer on basis of mismatch between AIR and F26AS Justified  Major Changes Expected in Direct Tax Code 2025 and why these matter

Major Changes Expected in Direct Tax Code 2025 and why these matter